Apalachee History of Florida

Apalachees of Florida

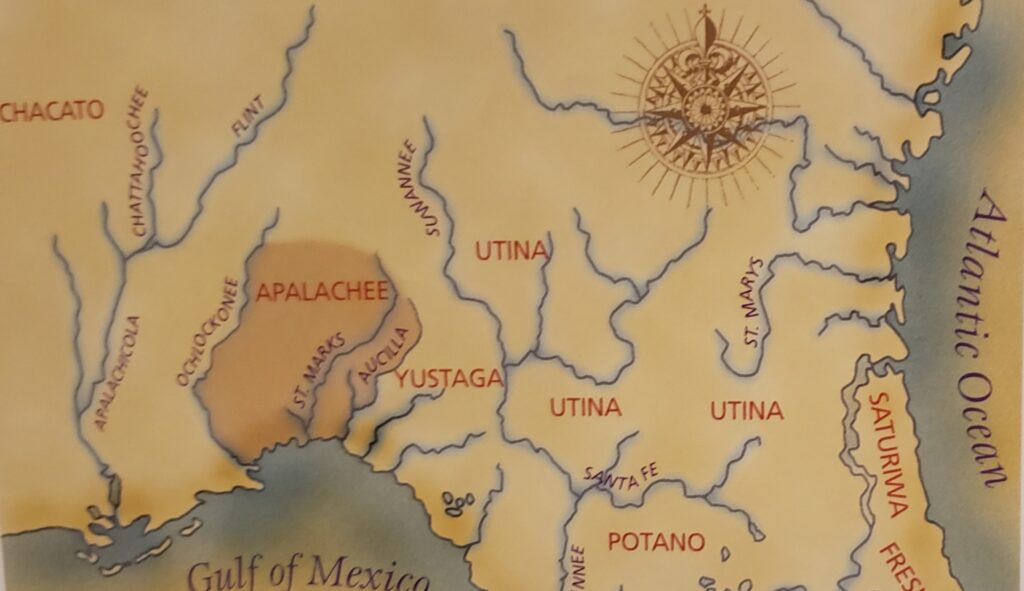

For thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, the people who would one day be called Indians lived throughout the North and South American continents. Many of them went through a series of changes over time – from simple groups that depended only on hunting game and gathering wild plants for food to more complex tribes that grew their own food. Some Native Americans eventually developed organized societies that rivaled those of Europe. The Apalachee Indians, who lived in the area around present-day Tallahassee, were among the most advanced and powerful of the Florida tribes that were met by early explorers.

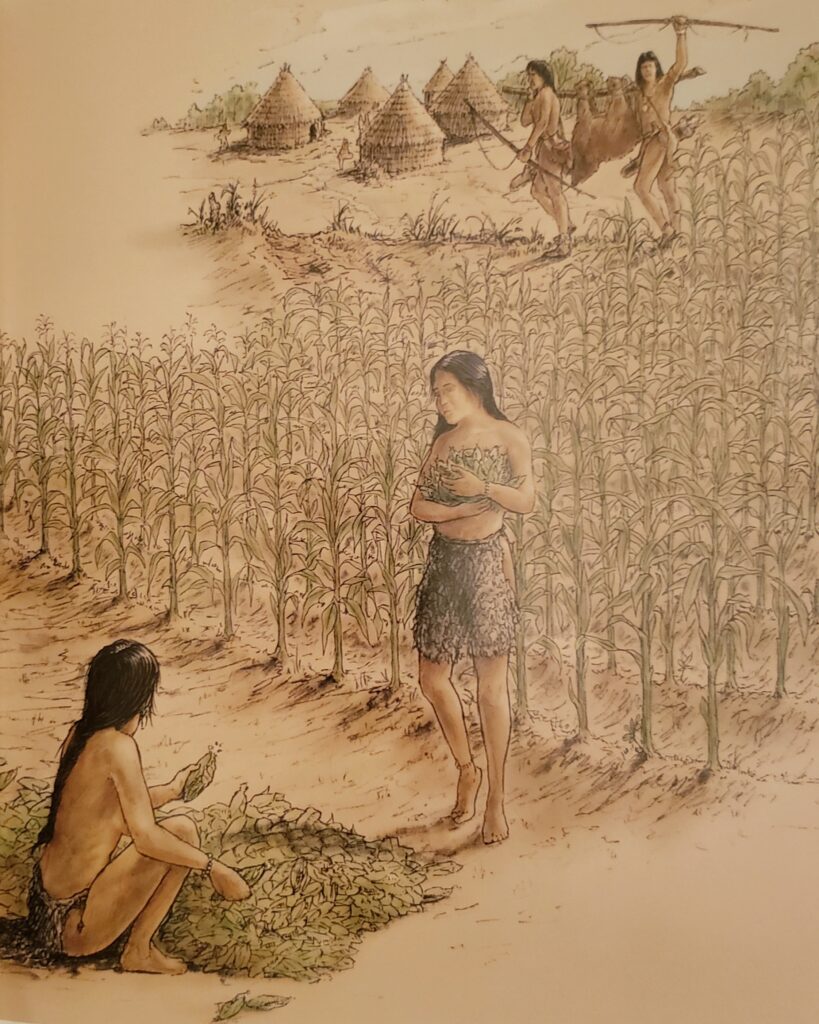

Before contact with Europeans, the Apalachee Indians planted corn (maize), beans, and squash, adding to this diet wild game, fish, wild fruits, berries, and nuts. These farmers built groups of palm-thatched huts close to agricultural fields where men, women, and children tended crops. In fact, the word Tallahassee is derived from the Muskogean language’s word for “old fields.”

Most work was assigned by gender and custom. Women did most of the farming, gathering of food, and food preparation. Men hunted wild game, fought in wars, and assisted in building and maintaining the villages. Childrearing was shared though much of the burden fell to women. Children worked alongside the adults, learning skills needed for everyday life. Still, children had time to play – boys shot arrows from bows; girls made baskets and clay pots. Everyone played ballgames, even the women.

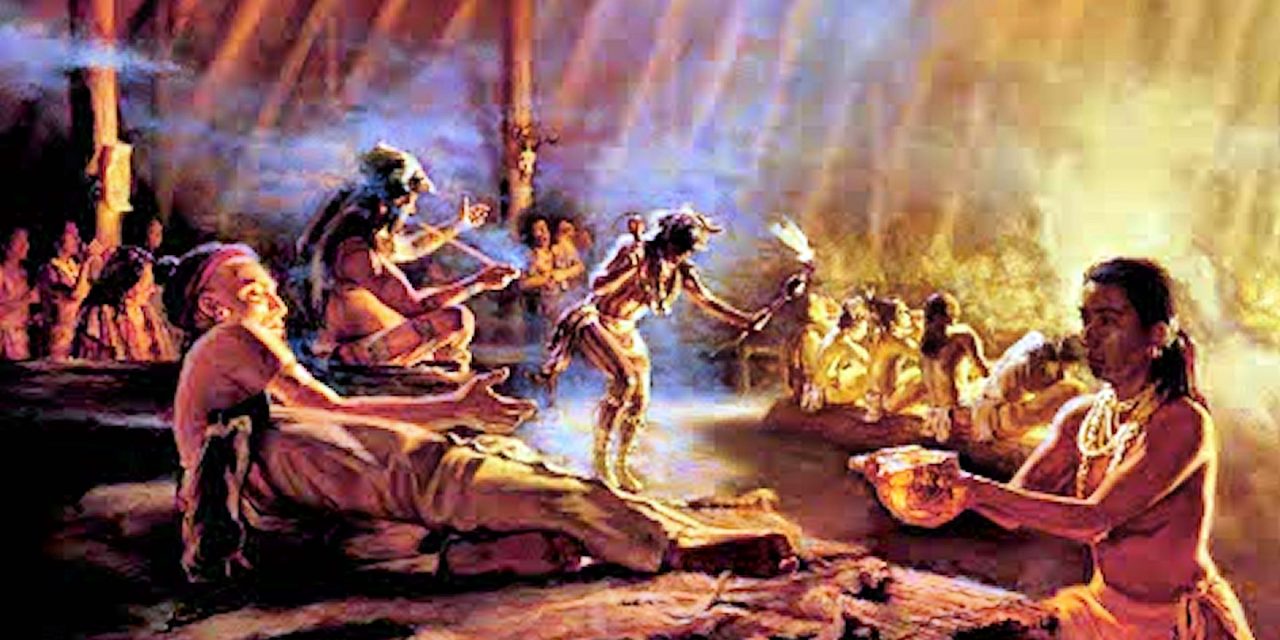

Apalachee society was well-organized and ruled by “chiefs” (holatas) who inherited their positions and were guided by priests. Gods representing natural forces guided the Apalachee religious beliefs and worship ceremonies. The sun, moon, rain, and thunder were thought to be divine since these were needed for growing food.

The Apalachee built large villages that included earthen “platform” mounds and plazas where religious and cultural ceremonies were conducted. They participated in a far-reaching trading network that brought them things made or gathered by other Native Americans beyond Apalachee Province – the metal copper is one example.

An Apalachee family placed more importance on the mother’s relatives than the father’s kin as was usually the custom in Europe. Native clans or extended families took the names of animals – deer, bear, snake – or natural forces – wind clan, for example. When an Apalachee man married, he resided with his wife’s clan.

Apalachee chiefs traced their inherited positions of power through their female relatives. When a chief died, his oldest sister’s oldest son inherited the position of chief. This custom granted more cultural status to Apalachee women than European women. Before their Christian conversion, chiefs might also have been the religious leaders of their people. The Apalachee chiefs governed villages and nearby fields and forests. The chief of San Luis was one of the most important in the province. Europeans described the size of San Luis as extending for miles around.

https://www.missionsanluis.org/learn/history/apalachee-before-european-contact/

Europeans Encounter Florida Tribes

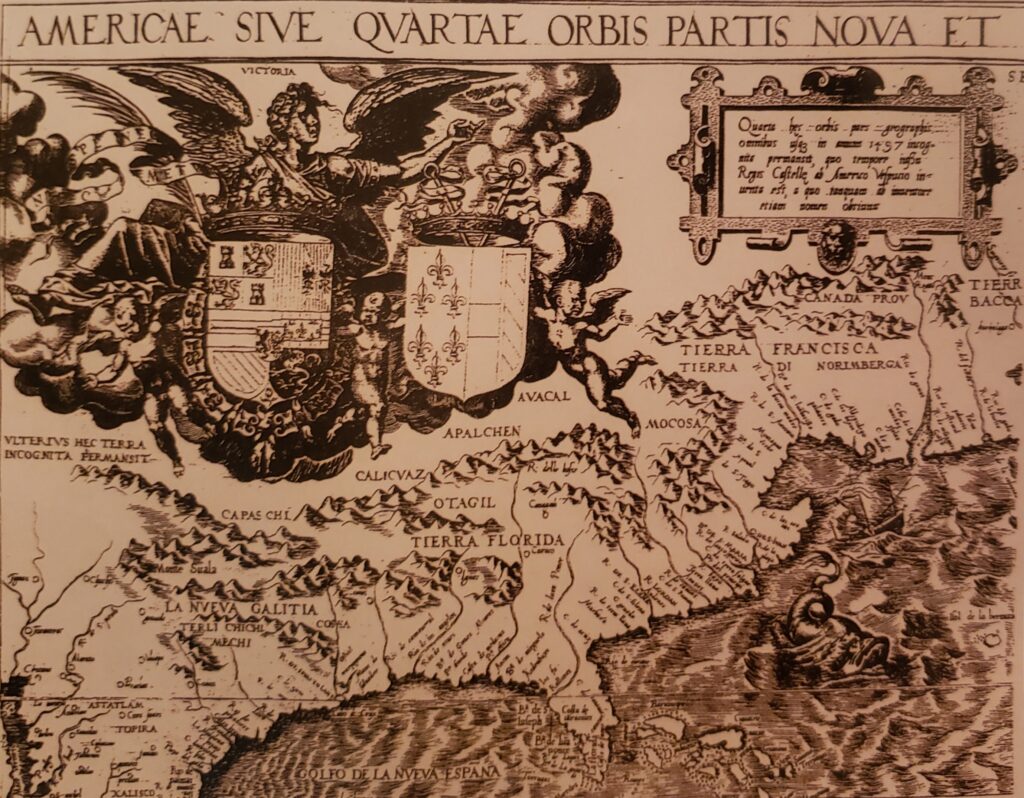

In 1497, John Cabot sailed along North America’s eastern coast possibly as far south as the Florida peninsula. Sixteen years passed before Spain’s Juan Ponce de León visited our state’s east coast in 1513 and west coast in 1521. He named the land “La Florida” and claimed ownership for Spain

The King of Spain said that La Florida extended from Key West in the south to Newfoundland in the north and over to Mexico in the west. The other European countries did not agree and reluctantly allowed Spain to rule wherever Spaniards made “New World” settlements.

In 1526, Lucas Vásquez de Ayllón founded the first Spanish settlement in present-day United States. He named it San Miguel de Gualdape. Its exact location is not known, but it was in Guale Indian territory along the present-day Georgia coast. The colony did not last long after Ayllón and most of the 600 settlers and slaves died. The 150 survivors returned to Hispaniola (Haiti).

This did not keep other adventurous Spaniards from exploring Florida and nearby lands. Dreams of great riches—like silver and gold in South America and Mexico—lured Pánfilo de Narváez (1528) and Hernando de Soto (1539) to seek their fortunes throughout the southeastern regions of La Florida. Native peoples in the Tampa Bay region told the Spaniards that riches could be found in the Apalachee Province. The de Soto expedition was the first from Europe to camp where Tallahassee, Florida is today.

With the Spanish noblemen and soldiers came Catholic priests to convert the pagan Indians to Christianity. These Spaniards found no riches. These priests converted no Indians. Most of the explorers died, but a few survived to tell Europe of their adventures.

The myth of Apalachee treasure was represented on early European maps by the name given to the Appalachian Mountains. Tragically, these European explorers and the many immigrants who came later spread diseases and germs that killed unknown thousands of Native Americans for many years afterwards.

In 1565, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés founded St. Augustine, Florida with the help of Timucuan Indians who lived nearby. Four centuries later, St. Augustine is North America’s oldest, continuously inhabited city. Menéndez chose this site on Florida’s Atlantic coast for military reasons. Spain needed to protect its treasure ships sailing through the Florida Straits from pirates and its European enemies.

https://www.missionsanluis.org/learn/history/european-age-of-exploration/

Spain’s King and Church

The King of Spain and the Catholic Church ruled Spanish settlements throughout its empire. Both government and religion increased power by collecting great wealth from Spain’s many colonies worldwide and converting the natives of those lands to the Catholic faith. Spanish society showed little religious tolerance to those who were not Catholics.

Yet, Spanish culture respected ethnic diversity. Intermarriage (mestizaje) between people of different races and cultures was common throughout the Spanish empire. From this is derived the term mestizo to identify a Hispanic person of mixed Spanish and Indian descent. Because there were few Spanish women in frontier Florida, Spanish men often married Indian women. Mestizos were likely an important part of mission society.

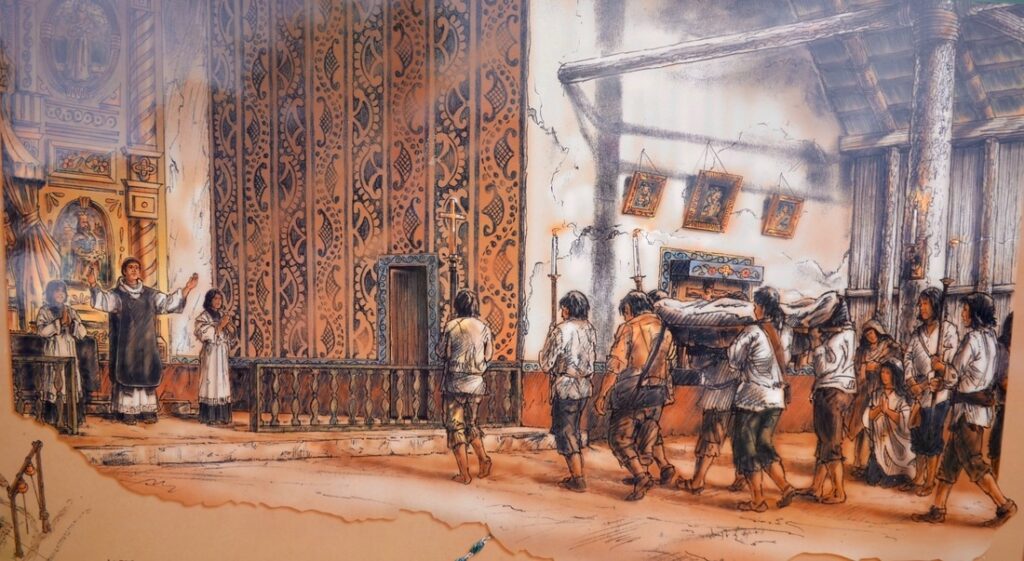

Religious missionaries to Spain’s colonies taught the Christian faith and maintained the people’s loyalty to the King. During Florida’s first Spanish colonial era (1513-1763), Catholic friars and priests founded over 100 missions in the southeast region of North America. Most of these wilderness churches were in small villages located along El Camino Real (Royal Road) between St. Augustine and Apalachee Province more than 200 miles to the west.

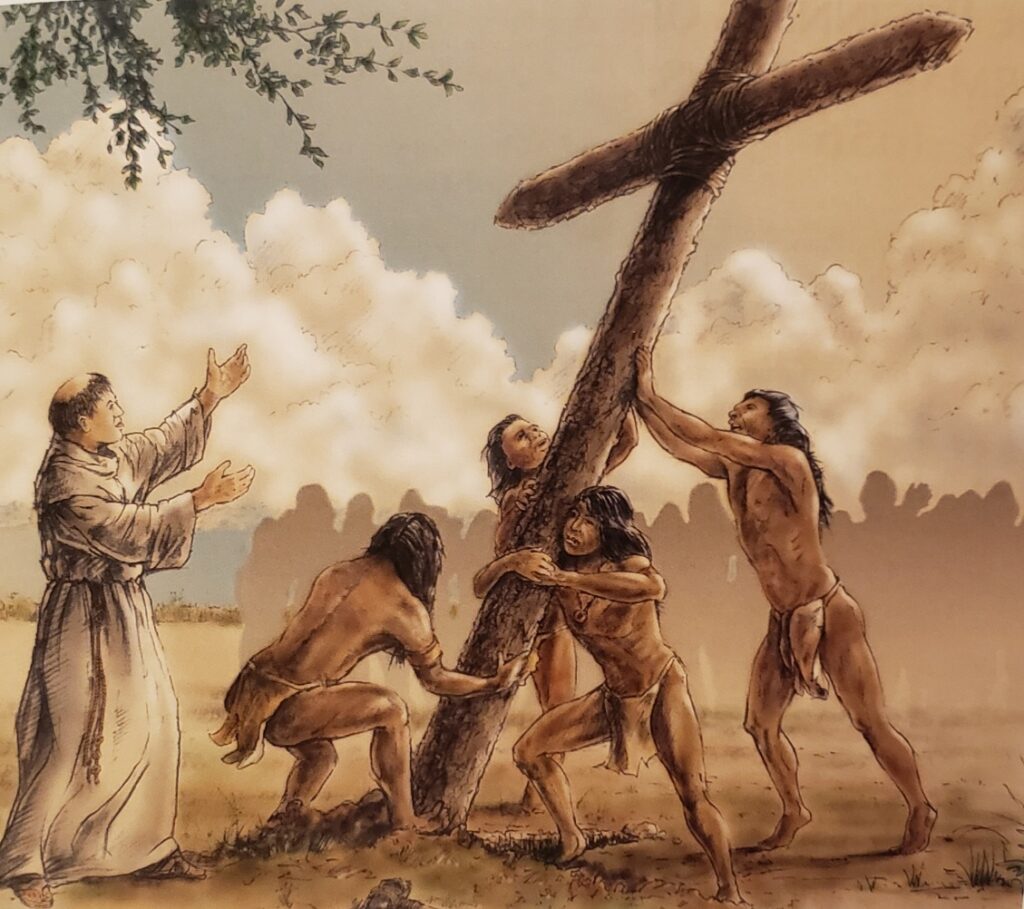

In 1607 some Apalachee Indians asked for Catholic friars to minister among the native peoples. By 1633, two Franciscan friars, Pedro Munóz and Francisco Martínez, founded the first two permanent missions in the province, and five years later the first Spanish soldiers arrived. San Luis, originally named San Luis de Inhayca, was probably among the first missions to be founded. The twin powers of church and state set about converting the province’s native peoples to Christianity and collecting wealth in the form of food grown in Apalachee to feed St. Augustine’s soldiers and settlers.

https://www.missionsanluis.org/learn/history/crown-and-church

Spanish Mission San Luis

During the Spanish mission period, Europeans thought the Apalachee Indians were the most advanced native peoples in La Florida. The Apalachee chiefdoms were among the most populous and powerful. The leaders and their assistants maintained relations (not always friendly) with other native peoples throughout the region.

It isn’t known why, but in 1656 Mission San Luis was moved to the second highest hill in present-day Tallahassee. Seeking to continue his political and military alliance with the Spanish, the chief of San Luis agreed to move his village and also to build a fortified house (casa fuerte) for a small garrison of soldiers. By 1675, this secondary location of the mission was called San Luis de Talimali.

When San Luis was built in 1656, the village resembled those that existed before Europeans arrived. The Apalachee leaders and their families lived in round, palm-thatched houses bordering the central plaza where ceremonies, business dealings, and ballgames were held. The largest Apalachee building by far was the council house that could hold 2,000 to 3,000 people. In the council house, the Apalachee and their chiefs met to govern the village, consider complaints, administer justice, conduct traditional rituals, and receive visitors.

The Catholic Church and its friary (convento) with detached kitchen (cocina) completed the main public buildings surrounding the central plaza. The church entry and the council house door faced each other across the circular plaza. This was a symbol of respect the Spanish government accorded Apalachee society and its leaders. The fort complex with its blockhouse and protective log wall (palisade) were a short distance away.

Apalachee families built groups of palm-thatched, single-room dwellings away from the plaza. These clusters of huts were closer to farm fields and inhabited by people who were related each to the other by marriage or birth. Living some distance away, these Apalachees journeyed to the central plaza for Saturday evening prayers, Sunday Mass, ball games, and other special events.

Spanish families, who began to arrive in significant numbers after 1675, lived in small, rectangular houses made of wattle-and-daub or wood planking with palm-thatched roofs. The Hispanic settlers built these two-room cottages (casitas) closer to the central plaza than the Apalachee dwellings. The Apalachees spent most of their time outdoors, using the huts mostly for sleeping. The Hispanic settlers spent more time indoors. Both probably often cooked outdoors over open fires. Only the friary had an indoor kitchen.

By contrast, St. Augustine and Pensacola were constructed around central squares bounded by a symmetrical grid of intersecting streets. Spanish ordinances decreed this urban plan for Hispanic colonial towns. The Hispanic settlers lived within town limits and the native peoples, if any, lived beyond the town’s borders.

https://www.missionsanluis.org/learn/history/mission-san-luis/

Native American Slavery

Both Spain and England participated in the slave trade of Native Americans and Africans to supplement their colonial labor forces. However, the Spanish government did not allow Florida Indians to be slaves as was the law and practice in other Spanish colonies.

Florida’s governors and its religious leaders allowed the Hispanic colonists to force Indians to work for little or no wages. Many natives were badly treated, poorly fed, and died of forced labor. Much of St. Augustine—the Castillo de San Marcos an example—was built by forced Indian labor.

Slaves were present in Florida, though not so many as in England’s Carolina colony where there were twice as many Africans as whites. Spanish law derived from ancient Rome and treated slaves and women differently than English common law derived from the Magna Carta of A.D. 1215. Under English law, a slave was property (chattel) that could be bought and sold freely and punished, even to death, without any legal or civil rights. English wives were treated as property of their husbands.

Spanish law recognized slaves as unfortunate persons who still had legal rights, could sue their owners in court, and could own property. Both men and women slaves could petition the Spanish King. The law allowed for slaves to purchase their freedom and to attain the rights of all the King’s free subjects. In Florida, the Spanish government granted freedom to escaped slaves from England’s American colonies if they converted to the Catholic faith and served in the colonial military.

St. Augustine had a free African settlement nearby, the first free black community in North America. Black slaves who escaped from the English colonies north of Spanish Florida settled together at Fort Mose. The men formed an armed militia to defend their families from English slave raids.

https://www.missionsanluis.org/learn/history/north-american-slavery/

Life in San Luis

From earliest European contact with the Apalachees, there had existed a native “capital” village in the vicinity of present-day Tallahassee. In 1539–40, the de Soto expedition recorded it as Anhaica Apalache “where the lord of all that land and province lived.”

In 1656, Spanish settlers and Apalachee Indians moved the village to its hilltop location two miles west of the present-day Florida State Capitol. Mission San Luis became the capital of the western Spanish missions and the Apalachee nation in La Florida from 1656 to 1704. Mission San Luis was one of early Florida’s largest colonial outposts.

Mission San Luis was the only settlement beyond St. Augustine where several hundred Spanish residents lived among Florida’s native peoples for three generations. The Spanish deputy governor and one of the most powerful Apalachee chiefs were among more than 1,400 residents. Spanish and Indian farmers, ranchers, merchants, and other trades people worked to survive and thrive in frontier Florida.

Most Apalachee men worked for the landowners as farmers, ranch hands, semi-skilled laborers, and possibly at a few skilled trades. Indian men served with Spanish soldiers in the Mission San Luis military garrison, protecting the Apalachee Province from rival tribes and their English colonial allies. These laborers worked long days at very tiring tasks and often without payment.

Apalachee women were treated a little better. They were Spanish house servants, unmarried companions, and even wives in Spanish and mestizo families. The children of an Indian-Spanish marriage were not forced to perform manual labor. Mestizo families held higher social esteem than Indian families. In letters from Mission San Luis, the Catholic friars complained of the Spaniards’ cruel treatment of Indians. Indians complained to government officials about beatings and other punishments from the Catholic friars, settlers, and soldiers.

https://www.missionsanluis.org/learn/history/san-luis/

Invasion of Fire

Even before the founding of St. Augustine in 1565, Spain, France, and England fought for control of La Florida’s southeastern borderlands. Beginning in 1670, Lord Proprietors appointed by England’s King Charles II founded Charles Towne (Charleston, South Carolina).

This Atlantic coastal village attracted settlers from the United Kingdom and its colonies, including Virginia and Barbados. It grew rapidly, and became a thriving commercial and military outpost on the English–Spanish colonial borderlands. Much of its riches came from buying and selling Africans in the Charleston slave market.

In 1687, English slaves began running away from Carolina plantations to seek freedom in St. Augustine. Spanish King Carlos II granted slaves’ freedom provided they became Catholics and obedient subjects. Even though the Spaniards practiced slavery, the King had a practical reason for freeing African slaves in 1693. The La Florida colony received new settlers while the English colony had fewer residents.

This practical act of humanity caused feelings between Spain and England to grow worse. The English slave owners demanded the return of their “property.” Spain did not do so. In 1701, England declared war on Spain and France. Historians named it the War of Spanish Succession in Europe, but Queen Anne’s War in North America.

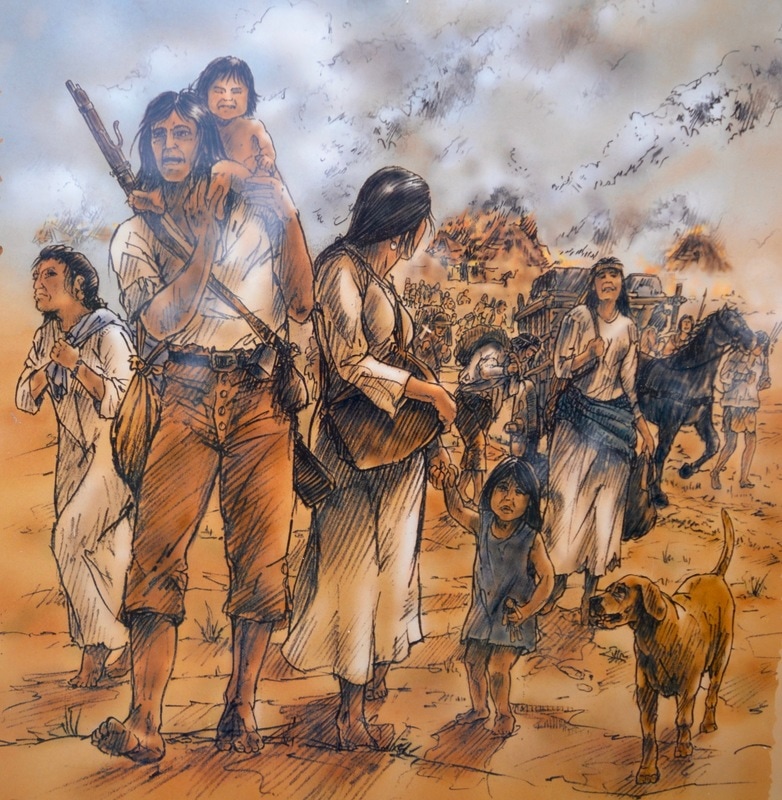

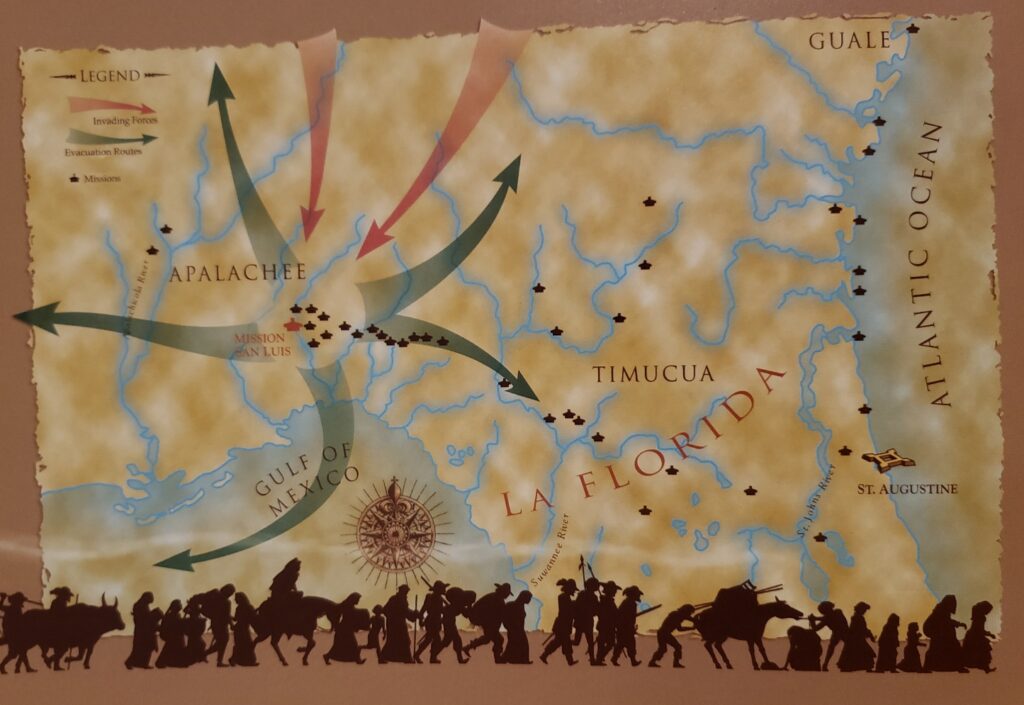

Battles between the American colonies of La Florida and Carolina nearly wiped out the Indians of Spanish Florida and southern Georgia and destroyed Spain’s network of over 100 missions. Five hundred English militiamen and 300 of their Indian allies attacked St. Augustine in 1702, burning the town, but failing to capture the Castillo de San Marcos. Most of the Spanish villagers and mission Indians survived inside the fort.

Mission San Luis was the best protected village beyond St. Augustine, and the English militia did not attack right away. With their Creek allies, English soldiers burned down the remote Spanish mission villages and killed or captured most Florida natives. Timucuan Indians in eastern Spanish Florida and Apalachee in the west were killed or enslaved in the English and Indian raids of 1703–1704. Most Apalachee who survived the English-led raids moved north and were settled on a Savannah River reservation.

By July 31, 1704 the English had marched very near Mission San Luis. Rather than allow the fort to be captured, the Spanish and Apalachee villagers burned all the buildings and fled. A few Apalachees traveled with the Spanish families to St. Augustine. About 800 Apalachees fled west from Mission San Luis to Mobile, a French village where they settled for a time.

https://www.missionsanluis.org/learn/history/la-florida/

The Apalachee Migration

With the missions destroyed, all that remained of Spanish Florida was St. Augustine. The English raiders drove Florida’s remaining Native Americans into slavery or exile. Nearly all Florida Indians in the Spanish colony had died of disease and in wars with other Indians and European colonists. Beyond St. Augustine, the rest of the colony was desolate and empty of Spaniards and Native Americans. So it would remain until Spain traded the Florida colony to Great Britain in 1763.

In Mobile, the Apalachee survivors of San Luis formed a Catholic parish and their French hosts provided a priest. On September 6, 1704, the first recorded Apalachee baptism took place there. Sixty years passed before 80 or so Apalachees moved from Mobile to central Louisiana.

They settled in Rapides Parish along the Red River. Time passed and these descendants of Mission San Luis disappeared from American history books for the next 200 hundred years. However, about 300 Apalachee descendants—today the only known descendants of Florida’s original inhabitants—have survived though not without considerable troubles.

The Mobile Apalachees survived a 1704 yellow fever epidemic. In 1803, American settlers in the Louisiana Territory burned Apalachee cabins and crops, stealing their land. In 1835 the Louisiana Apalachees fled to swampy bayous and remote hill country, withdrawing from white society. Some of this group found that life was easier for them if they hid or even denied their Indian heritage.

https://www.missionsanluis.org/learn/history/apalachees-in-exile/

Apalachee of Louisiana

Today in Louisiana, the Apalachee have become an organized community that continues to research the tribe’s past as well as develop new techniques to cultivate awareness on our existence in the 21st century. With the governing body of the tribe residing in Louisiana, the Apalachee stretch as far as California and Virginia, and as close as Texas and Florida. Apalachee were declared an extinct tribe for over 130 years. With our resurrection, we can now share our story as one of the first tribes to come in contact with Europeans. We can also demonstrate the perseverance and tenacity it takes to become one of the last tribes in Louisiana pursuing full recognition in the United States Supreme Courts. We stand strong and united, for we are Apalachee!!!