Apalachee History of Louisiana

Louisiana Under French and Spanish Rule

In 1762, the last year of the French and Indian War, Spain joined France against England and that year Spain lost several of its New World possessions. France, with its treasury drained from the long conflict and suffering numerous defeats over the last years, was anxious to end the hostilities. Spain, however, was eager to retain what the British recently had taken from it. France secretly ceded Spain all of Louisiana west of the Mississippi River with the singing of the Treaty of Fontainebleau in November of 1762. This cession also included the Isle D’Orléans which encompassed that portion of Louisiana east of the Mississippi, south of the Iberville River, and the valuable port city of New Orleans.

The conclusion of the war, culminated by the signing of the Treaty of Paris of 1763, brought about many changes in the Southeast. Havana reverted back to Spanish Control, the British Gained Florida, and France forfeited that portion of Louisiana east of the Mississippi to England. As a consequence of this and her losses in Canada, France’s role as a colonial power on the North American continent ended.

(King and Ficklen 1893:110-112, 113-114; Martin 1975: 189-193, 196-200; Schlesinger 1983: 97)

With the French evacuation of Mobile, AL and the British occupation, many of the small tribes residing in that area petitioned the French administrators in Louisiana to move west of the Mississippi river. the British and their Indian allies, especially the Tallapoosa, were old enemies of these small bands. With the French gone from Mobile, there would be no one to stop Indian reprisals or prevent the enslavement of those bands who had supported them.

The Apalachee were one of the first groups to petition Louisiana’s Director General Jean Jaques Blaise D’abbadie and Governor Louis Billouard de Kerlerec to immigrate to Louisiana. On September 6th, 1763, a deputation of Apalachee arrived in New Orleans and met with two administrators. D’abbadie noted that these Indians were all afraid of reprisals from the Tallapoosa because they had assisted the Spaniards in apprehending one of that tribe. He observed that they were both good farmers and hunters who would be desirable to have this band settler in Louisiana andto place them on the Red River where they could also assist boats ascending the river to Natchitoches. The Apalachee returned to Mobile, AL with a letter written by D’abbadie instructing the French commandment there to allow the Indians to move.

On September 25th, 1763, the Apalachee returned to New Orleans and again met with D’abbadie and Kerlerec. There was a meeting held on September 27th and on that same day the Apalachee departed for Red River. On the same day, the Apalachee elected a new chief named Martin because their current chief was believed too old for the position. That day the French provided them with boats and guides to the area known as Rapide.

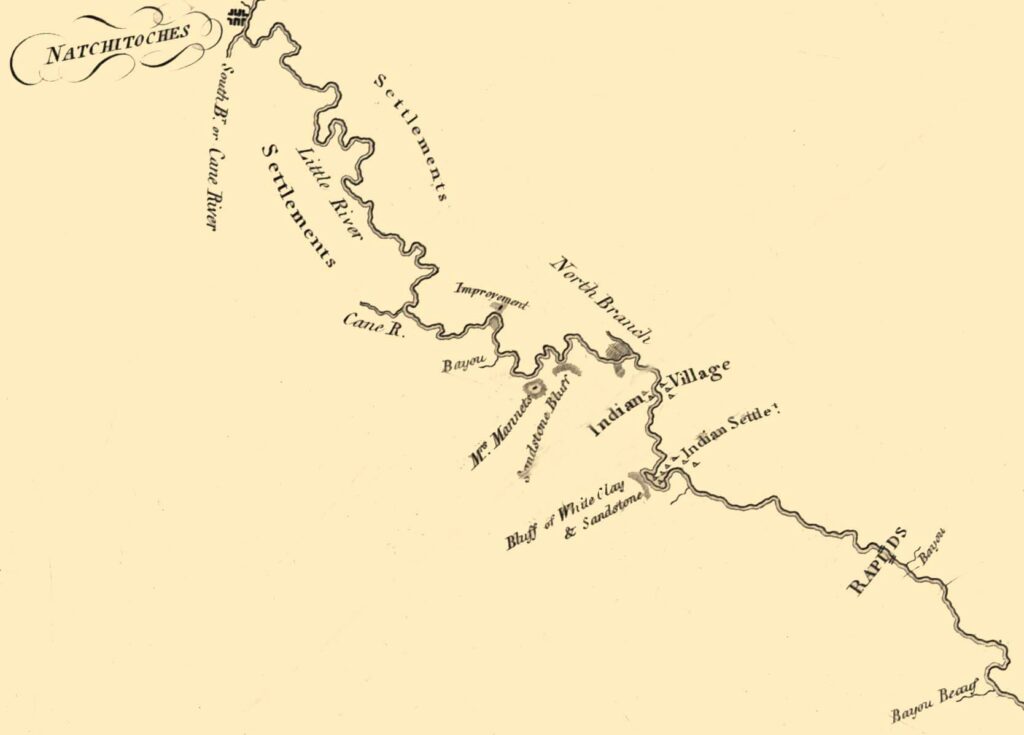

Rapide (later to become Rapides Parish) derived its name from a set of large siltstone shoals or rapids in Red River near the present city of Alexandria, Louisiana. In fall of 1763, it was a sparsely settled area located approximately midway between the mouth of the Red River and Natchitoches. The French had made no establishments there before that time and the district was devoid of any substantial Indian or European settlement.

Little has been learned of the Apalachee during their first four years on the Red River. Primarily because there was no colonial administrator there until 1767. That year Governor Ulloa established a post at Rapide under a civil and military commandment ran by Etienne Marafret Layssard. He held the position until his death in 1793 at which time his son, Valetine, was appointed as his father’s successor and the district Indian agent.

(Brasseaux 1981: 100-102; Villers du Terrage 1904: 61; De Ville 1985; 6-8; Lowrie and Franklin 1834: 661)

(Donald G. Hunter; Their Final Years: The Apalachee and Other Immigrant Tribes on the Red River, 1763-1834. The Florida Anthropologist, Volume 47, Number 1, March 1994 pages 3-5)

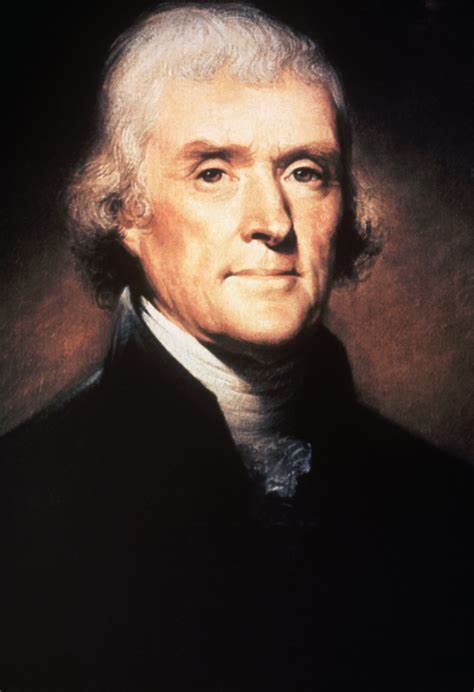

United States Purchase of the Louisiana Territory

By the dawn of the 19th century, Spain had been involved in costly European wars for several years and her resources were effectively diminished. Louisiana had become an expensive luxury that must be sold before England or the United States took it by force. On October 1st, 1800, the Treaty of San Ildefonso was enacted retroceding Louisiana to France in exchange for conquered lands in Italy to be awarded to Spain. Napolean envisioned Louisiana as an agricultural complement to Santo Domingo, giving France control of valuable cotton and sugar production. However, a slave revolt on the island prompted Napolean to sell Louisiana to the United States. Thomas Jefferson understood that control of the port of New Orleans and the Mississippi River were necessary to further American expansion. On April 30th, 1803, the United States acquired the Louisiana territory for the price of $15 billion. Conditions of existence for the Indian nations of the southeast would be dramatically and irrevocably changed.

American Intent for economic development in Louisiana was neither as opaque nor as haphazard as that of the Europeans. Although enlightened and humanitarian by nature, President Jefferson gave little regard to the Indian inhabitants of Louisiana when weighing the agricultural bounty that the territory could provide the United States.

The value of the Mississippi River valley extended not only to agriculture, but also to exploitable natural resources, primarily timber and numerous waterways. Not indifferent to the plight of Indians whose lands were daily being encroached upon. President Jefferson expected that the tribes would continue westward into vast expanse of territory beyond the Mississippi River valley. Treaties designed to force Indians to vacate ancestral lands were implemented by frontier officials empowered by President Jefferson.

Immediately after the Louisiana Purchase was in effect, thousands of American immigrants moved west of the Mississippi. The territory around Orleans, set aside in 1804 in the southern portion of the purchase area, saw 14,000 immigrants arrive within five years. By and large, the newcomers sought land on which to build an agricultural empire. From New Orleans north and west cotton and sugar plantations built primarily upon slave labor flourished.

Indian Agent of the Orleans Territory

Dr. John Sibley came to Mississippi River Valley in 1802 and integrated himself with William C.C. Claiborne, then Governor of the territory of Orleans. When Dr. Sibley arrived in Natchitoches in 1803, he began to gather knowledge on the area and the Indians from traders who served as middlemen.

This knowledge would serve him well and in 1805 he was appointed Indian Agent for the territory of Orleans. Sibley was instructed to cultivate the friendship of the tribes, and to assure them that the surveyors sent onto their lands would not inhibit their rights of ownership. The Secretary of War wrote to Sibley: “Their several titles, to the respective tracts of land, will be held sacred; and no person or persons whatsoever will be allowed to molest them, or take from them, one acre of their lands, in any way, except by their consent, and fairly & honestly agreed to by the respective nation, at public treaties held under the immediate direction of the Great Father.” Under the guise of protection, the stage was set for the wholesale acquisition of Indian lands which began almost immediately.

Because Spanish officials continued to administrator Louisiana during the retrocession to France, the laws of Spain enacted under Governor Alejandro O’Reilly in 1769 remained in effect. As delineated by congress in the Organic Act of 1804, all laws in force in the territory at the time of purchase were to be continued until altered by the territorial legislature. In 1805, a committee was established to draft a civil and criminal code for the territory.

Not until 1825 was a new civil code adopted in Louisiana which officially repealed the laws in force. However, two decisions made by the Louisiana Supreme Court after 1825 Civil Code was enacted held that preexisting laws were not repealed unless contrary to the provisions of the new civil code. In an 1839 decision the courts went further, concluding “that the Spanish and the French civil laws, which the legislature repealed, are the positive, written, or statue laws of those nations, and of this state. The Legislature did not intend to abrogate those principals of law which had been established or settled by the decision of courts of justice.”

(Billington Ridge 1982: 2435, 409-10; Purser 1964: 404; Carter 1940: 449-50; Juneau 1983: 28-31; Judge Martin in Juneau 1983: 33-4)

Apalachee Dispute of Illegal Land Sale

Explicit in the corpus of Spanish laws which Louisiana courts considered to be in force were those protecting Indian lands and tribal rights of ownership. Creole judges were accustomed to the Spanish tradition of cordoning tribal land from that of settlers; but, despite professions to protect Indian lands from whit incursions in American courts of law, Spanish protective measures would be misinterpreted and manipulated to legitimize white claims to Indian lands.

The Apalachee purportedly sold their land to merchants Alexander Fulton and William Miller in 1804, but the sale was disputed almost from the beginning. Spanish Commandant Valentine Layssard had awarded exclusive rights to trade with the Indians of the Rapides district to Fulton and Miller, to whom the local Indians quickly became indebted. In order to pay their debts, many of the small tribes had relinquished their lands to the merchants and consolidated on Bayou Boeuf by 1802.

In 1803, a group of Taensa and Apalachee informed Layssard that they sold their Red River lands to Miller and Fulton to satisfy a $2,600 debt and to acquire merchandise of an equal value (later changed to a cash payment). Representing the Apalachee was Louis, Chief of the Taensa, who had settled with the Apalachee on Red River by 1788 and who was married to an Apalachee woman. Layssard supposedly had verbal authorization from Etienne, the Apalachee Chief, who was not in attendance. Louis Taensa’s authority to represent his wife’s people was later disputed by the Apalachee, who vowed they had never given authority to anyone to sell their lands.

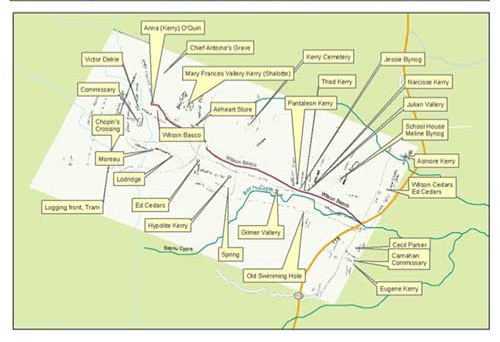

Shortly after the land sale was enacted, the Apalachee split into an upper and lower division. The upper group though to be settled with the Coushatta near present day Shreveport and the lower remaining at their Red River village site, then supposedly owned by Miller and Fulton. The two merchants were apparently content to allow the Indians to remain at their village site. Sibley noted in 1807 that 33 Apalachee and 18 Apalachee from the “upper village” were among several groups receiving provisions in Natchitoches. Presumably, the 33 mentioned first were those still settled in Rapides.

(Juneau 1983: 38-47; Hunter 1985: 23, 1994: 14,17-18; ASP, PL II 1834: 796; Sibley 1922: 39)

In his report on the local Indian groups in 1805, Agent Sibley described the Apalachee:

“Apalachies, are emigrants from West Florida, from off the river whose name they bear; come over to Red River, about the same time the Boluscas (Biloxi) did, and have since lived on the river, above Bayou Rapide. No nation has been more highly esteemed by the French inhabitants; no complaints against them are ever heard; there are 14 men remaining; have their own language but speak French and Mobilian.”

In regard to the disputed Miller and Fulton claim, Dr. John Sibley submitted a letter to the U.S. land commissioners, dated January 20, 1814:

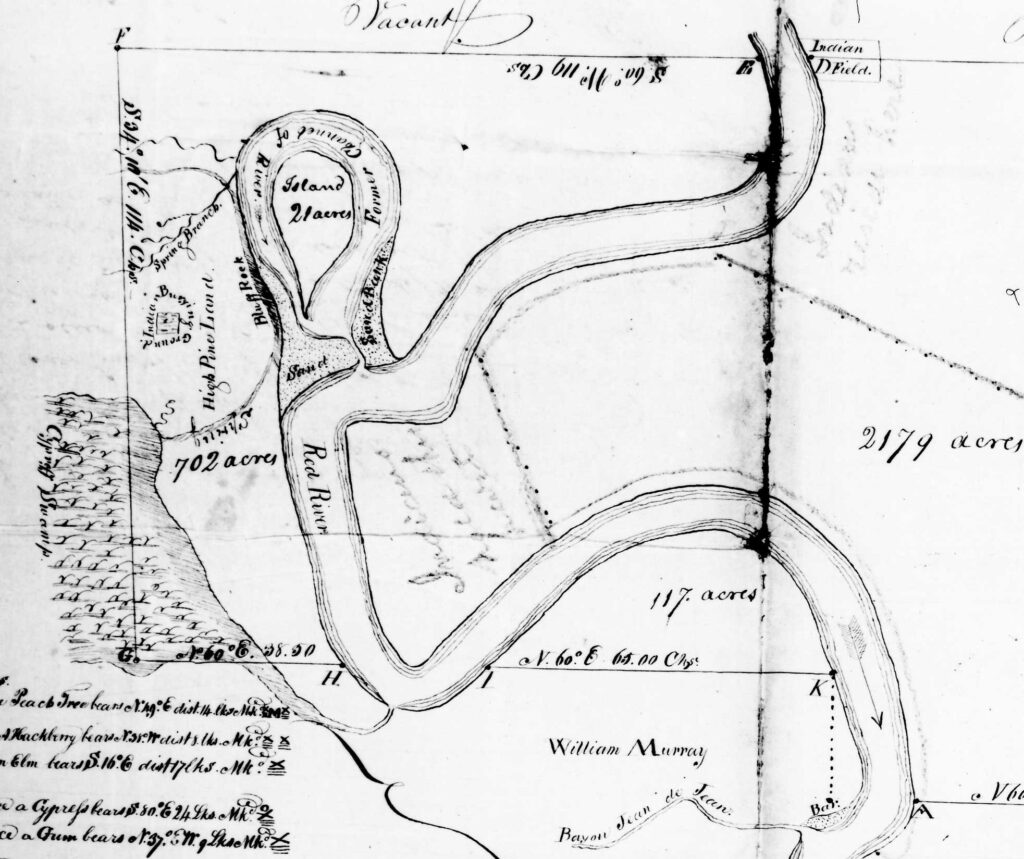

” Captain Louis, the chief of the Appalaches village, or tribe of Indians, who live on Red River, about 20 miles above Rapides, has just been with me, with a number of principal men of the village, to represent that Colonel Fulton and his associates are making them uneasy on their lands. They state that, after the transfer of Louisiana to the United States, they are continually advising them to sell their lands; that the country then belonged to the United States, who would take it from them, and give them nothing for it; that they could find, at that time, nobody who could advise them better; and that, finally, they consented and did pass, to them a sale for the consideration of $3,000, which has never been paid any part of it. If their statement is correct, by the law of the United States the sale is not only null and void, but the purchaser is guilty of a misdemeanor for which a penalty is incurred. They state that Colonel Fulton and his associates are pursuing their claim before your board. It is proper for me to state these facts to you which I have other reasons than the Indian story to believe are true. In the year 1805, I received some special instructions from the Executive of the United States relative to Indian lands, to prevent white people from disturbing them, or encroaching upon them. The lands of the Appalaches I had surveyed by a public surveyor, a plat made, a copy of which is filed in the War Office at Washington, and was approved by Government, and I shall do all that is Incumbent on me to protect the Indians, even by calling on the military should it be necessary.”

Unfortunately for the Apalachee, Sibley was replaced as Indian Agent shortly thereafter, due in part to his attempts to protect the rights of the Indian groups within his agency. However, the survey referred to by Sibley conducted to delineate Apalachee lands was made three years after the time they had purportedly sold their lands to Miller and Fulton.

On June14th, 1814, Chief Louis and principal men, Faluktee and Baptiste (probably Jean Baptiste Vallery), filed a formal complaint with the U.S. Land Office in Opelousas. They charged that miller and Fulton had not paid for the land they had supposedly purchased. The Apalachee denied having been indebted to the merchants, but they confirmed that the Coushatta living among them had been. They told the commissioners at the time that their village contained about 25 families who divided their time between hunting and agricultural.

The commissioners had already taken action on the disputed lands. A year earlier, they had recommended that title be confirmed to Miller and Fulton for the Taensa’s land only. Instead of being returned to the Apalachee, however, the land which included the Apalachee village was sold by the United States as public land to Issac Baldwin.

A New Threat

Alexander Fulton died in 1818, the same year his partner William Miller, left Louisiana. They sold their claim to Issac Baldwin, who established his Village Plantation below the Apalachee village. Approximately 150 Apalachee and Taensa still occupied the Red River land at that time. Baldwin began immediately to try to evict the Apalachee and Taensa from their lands. He first attempted to have the U.S. War Department remove the Indians. When those efforts proved futile, Baldwin engaged Congressman Josiah Stoddard Johnson to have the Indians removed from his claim. Through Johnson, Baldwin was able to successfully remove some of the Indians from the limits of his plantation.

(ASP, IA. IV 1832: 724; ASP, PL, III: 218; ASP, PL II 1834: 796; Hunter 1985: 26)

The Apalachee were offered swamp land on Catahoula Lake, which they refused. The government then attempted to persuade them to locate to Oklahoma, just prior to the forced Indian removal period beginning in the 1830’s. Jean Baptiste Vallery travelled to Oklahoma to see what his people were being offered.

” I understood he went up there by himself, and they wanted to know where the rest of his people were, but he wasn’t about to bring them up there. He found out they were starving the people to death there. It wasn’t like they said. So, he just got on his horse and rode back to Louisiana.”

(G. Bennett interview, March 10, 1998)

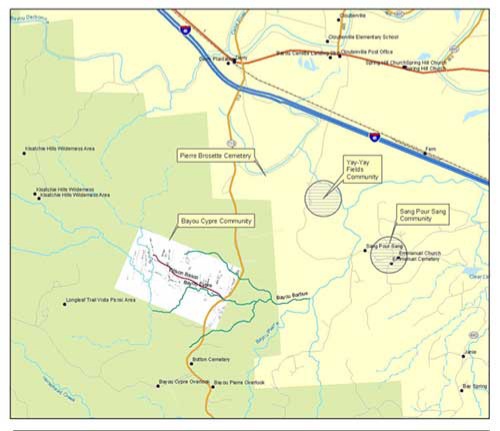

From this point forward, the Apalachee would suffer intense persecution at the hands of their white neighbors, causing them to retreat further and into marginalized ecological and occupational safe zones in the Kisatchie Hills of Natchitoches Parish. Although Baldwin denied responsibility, a cabin belonging to an Indian named Baptiste, one of the village headmen, was burned in 1826. The dispute continued for several years, and in 1832, Indian Agent Jehiel Brooks recommended that title to Apalachee lands purchased by Issac Baldwin undergo legal investigation and that the sale be cancelled.

” Some years before the cession of Louisiana to the United States an Indian of the Taensa tribe who married an Apalache woman sold a valuable tract out of the Apalache land on Red River, but the Apalache Indians Have never admitted the right of the Taensa Indian to make the sale. In 1830 owing to some great oversight or false representation of the Indian claim, a deputy surveyor surveyed the residue of the Apalache tract, and even made return of the ground occupide by their village and corn fields as “wood land,”

and the same was sold as such in November of that year, at Government price. Issac Baldwin was the purchaser who has since assured me that he would not take it for $20 per acre.”

Despite the protestations of the Indian Agent, Baldwin continued his efforts to evict the Indians from the land he had purchased from the United States. Baldwin admitted in 1826 that he had been able to drive all but five or six families off of his lands, on which no more than thirty remained. Indian Agent George Gray stated in 1827 that depredations by Baldwin had driven at least ten families of Apalachee and Taensa into Texas.

Patents to the lands had still not been issued by 1832, but the Apalachee were apparently no longer inhibiting their village site when they petitioned the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives for reparations in 1834.

(Hunter 1985: 27-8; 1994: 29-31; Bailey 1834)

Unresolved End

The Apalachee Indians residing in the state of Louisiana and parish of Rapides on the left bank of the Red River most respectfully states that they have inhibited the above named place for the last 80 or 90 years, that we had made considerable improvements in building our village besides improving and cultivating the lands, that sometime in the year 1830 our lands was offered for sale at the land office, when one Issac Baldwin became the purchaser of all our village together with the land. Shortly after which time our village was burnt, our farmlands wasted, and our women and children driven from our lands by the said Baldwin.

It is difficult to decipher the names of those who signed the petition, but they appear to be Ballace Tinsaw, Louis Acoye, Louis Appalach, Joseph Joahaw (Jouafa), Antoine Shirley (Vallery), Julian Jose Lawes, and Lauran (Lorenzo) Acoye. Alternate spellings are suggested from Apalachee baptismal records from 1815 found in the Natchitoches parish church records. No action was taken by the government to help the Apalachee, but title to the land would remain under dispute.

(Dayna Bowker Lee Ph.D. The Apalachee in Louisiana after 1800. April 30, 1998 Pages 1-12)